I recently returned to three images that have a lot in common for me as they sum up my understanding of recovery when applied to the subject of mental health and wellbeing.

The first is this tree. I used to see it every day in the grounds of the Saint John of God Hospital in Dublin, where I worked for MHFA Ireland

As you can see this tree has not had an easy life. It’s had plenty of knocks along the way, bares quite a few scars and it seems clear that things have been pretty much touch and go at periods in its life. Yet here it is now and we can all see that it is flourishing.

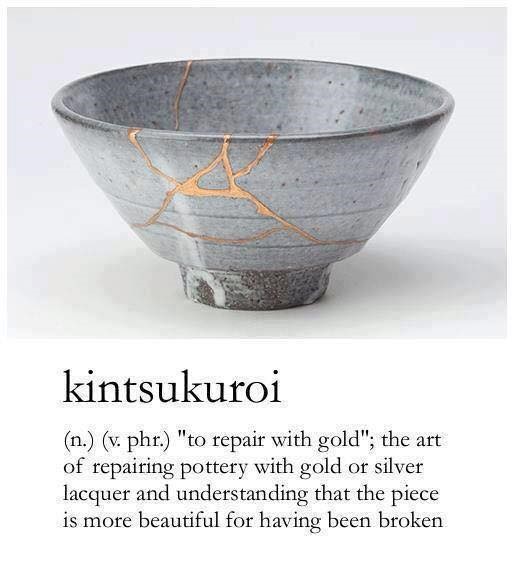

The second is this. I have been lucky enough to have been to Japan a couple of times and I find the culture fascinating. I have to admit that I did not know about kintsukuroi until I discovered the image, but the explanation made me think. When a person goes through emotional and mental distress it can feel to them like they are broken but with the right kind of support, they can come out of the other side stronger than before and with a better understanding of their individual risk factors and protective factors that can make a difference in maintaining and improving positive mental health. This message, that people can and do recover from mental health problems is a powerful one. It is a message of hope and hope is something we all need in our lives so, even though it can be hard for the person to believe at the time, it cannot be stated enough. However, they cannot do this all alone and that is where the third image comes in.

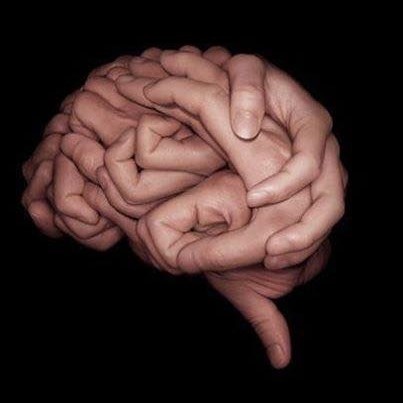

I found this several years ago and anyone who has attended any of the training I have delivered in the UK or Ireland will probably recognize it as it is the wallpaper on my laptop. It is also my profile picture on both Linked In and Facebook. I remember taking a few seconds to realize that the brain was made up of hands when I first saw it and that immediately resonated with me.

One of the things that people experiencing mental health problems often report is that they feel like they have been abandoned. This can be for a number of reasons. A lack of education about mental health can lead people to fall back on the negative stereotypes promoted by the media to form their attitudes toward a person with a diagnosis and they might be fearful of how that person might behave. The currently dominant paradigm of a disease/disorder model around mental health issues can also lead some to be afraid that this could be somehow infectious. Equally, because this model binds the subject up in jargon and complexity, people can distance themselves from a person with a diagnosis for fear of making things worse as they are not a professional in the field. Research into subjective wellbeing has shown that social support is one of the most important factors in producing positive mental health. That is hardly surprising as we are mammals and therefore social

beings. The image tells me why I and a lot of other people do what we do. The purpose of my work is to unpack all the myths and misconceptions that surround mental health for a lot of people, to challenge the medical model, to normalise, to humanise and to help people empathise. Once the mystery is gone it is a lot easier to be there for each other, as we really are all in this together.

While I was delivering MHFA training in Ireland people would often express dismay at the level of mental health services at the beginning of the course. I used to try to emphasize that what we were about to do was to look at what we had, what we could do with what we had, and, perhaps most importantly, what we could do for each other.

This final image seems to be a proper conclusion.